post-patient

CT scans and other imaging tools allow us to literally see physical health problems. But cancer also leaves impacts we can’t see. This exhibition exposes the pervasive mental health toll as well. Graphic design is a powerful tool for visualizing ideas. And to engender post-patient empathy, ideas are exactly what need to be exposed. post-patient is a three-part experiment using design to visualize thoughts, and open conversations.

Upon mentioning cancer, inevitably I was met with stories of an aunt, friend, coworker, or parent affected by the disease. The willingness to share was ultimately an attempt to connect. People need to share their stories. We connect through conversation. This key observation led me to wonder: How can graphic design not just talk, but also listen?

Completed as my MFA thesis project at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Thanks to mentors Jason Gottlieb, Ellen Lupton, and Jennifer Cole Phillips. Support from Abraham Burickson, Lili Maya, and visiting critics Jessica Helfand, Zach Hobbs, Jeremy Hoffman, Ayden LeRoux, Abbott Miller, Rianne Petter, and Mark Mulder.

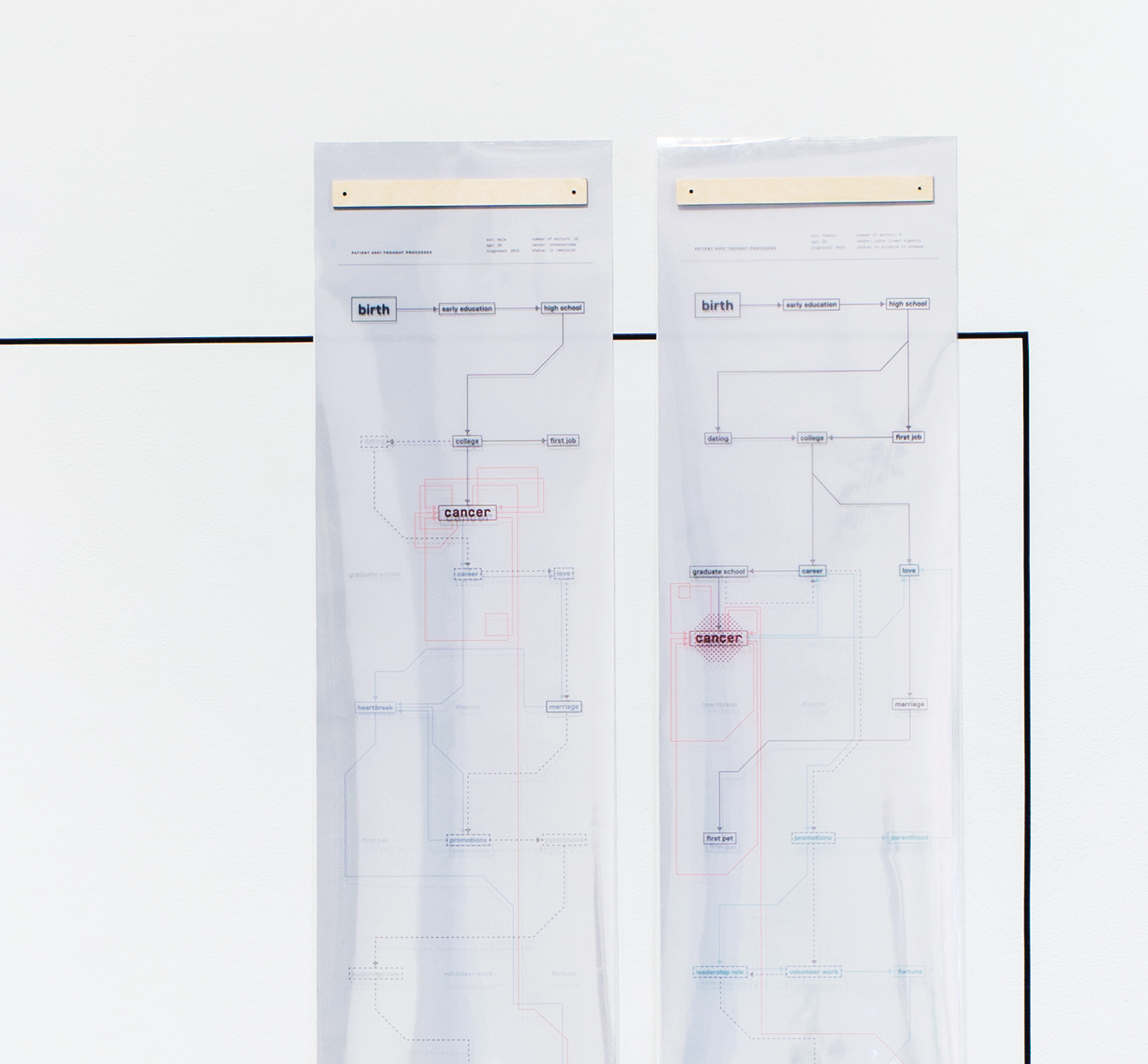

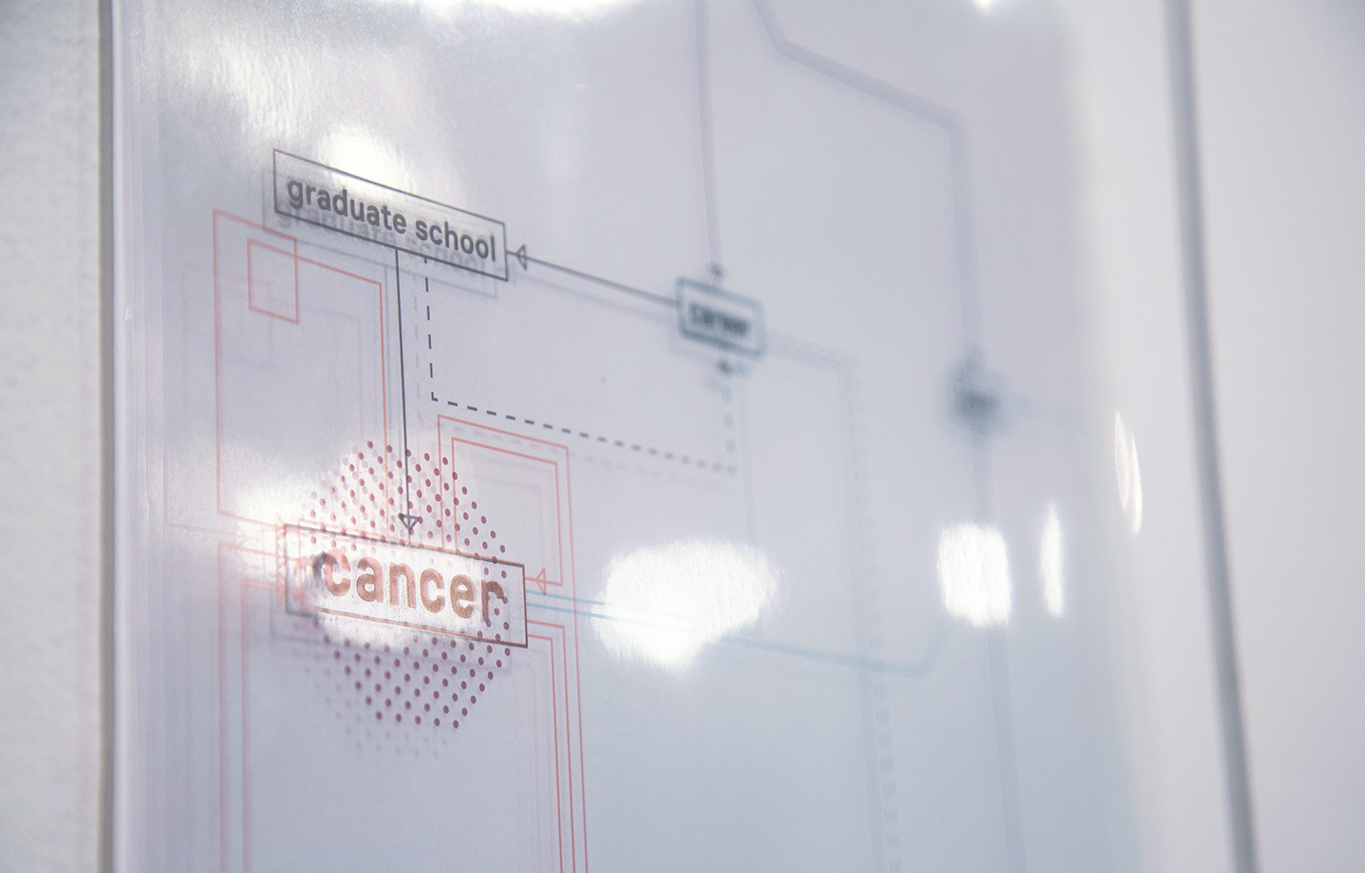

section one: an impasse

There are three common mental health diagnoses for cancer patients: fear of recurrence, survivor’s guilt, and Damocle’s syndrome. In order to visualize how a mind can wander under these distinct diagnoses, a system of transparent timelines were created. Patient milestones based on real survivor feedback are overlaid with imagined future paths. These are not their potential futures; rather, they are the wandering thoughts a patient may experience under different mental states.

After cancer treatment, one may feel as if anything is possible. But for some survivors, that’s not always a good thing.

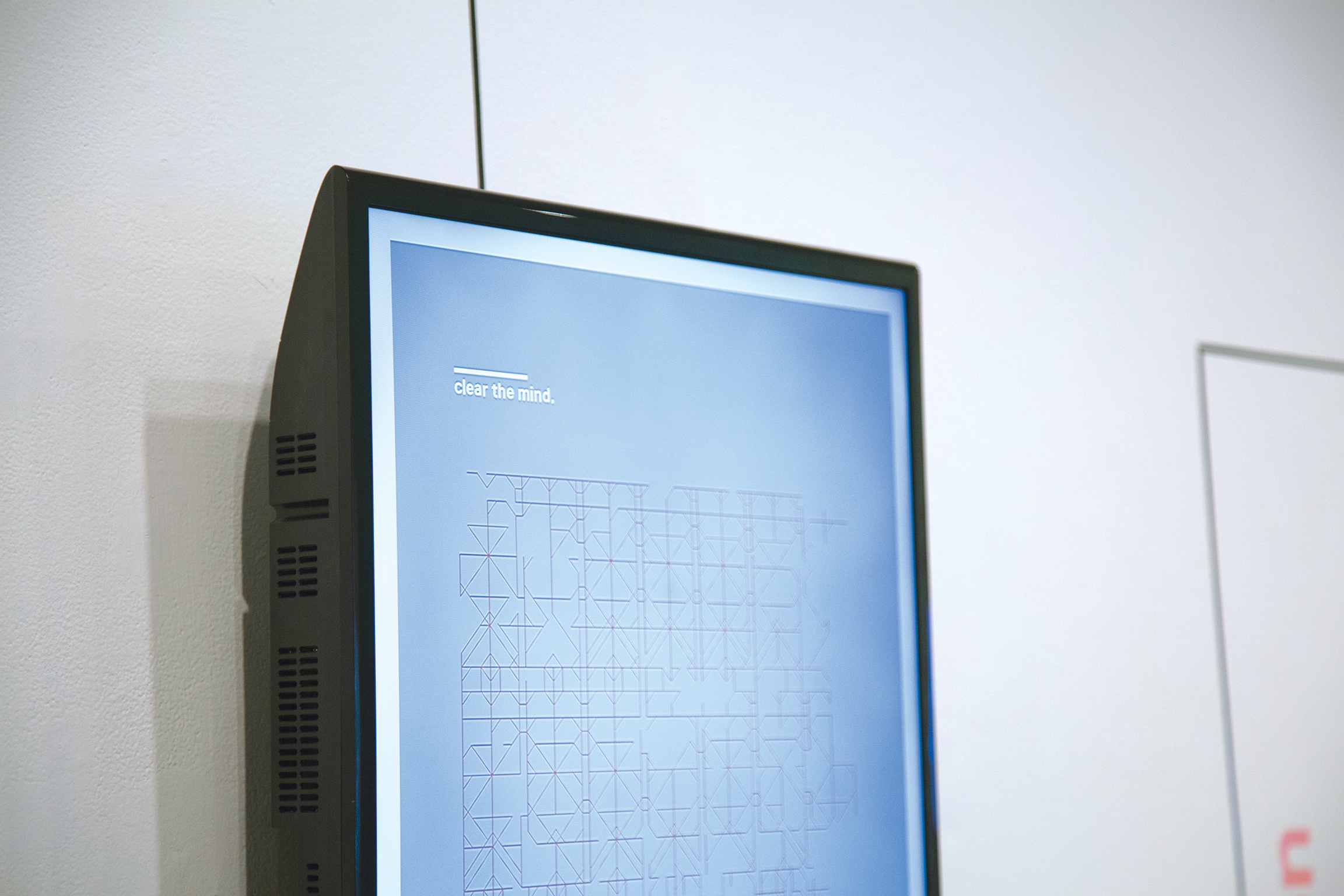

section two: your impact

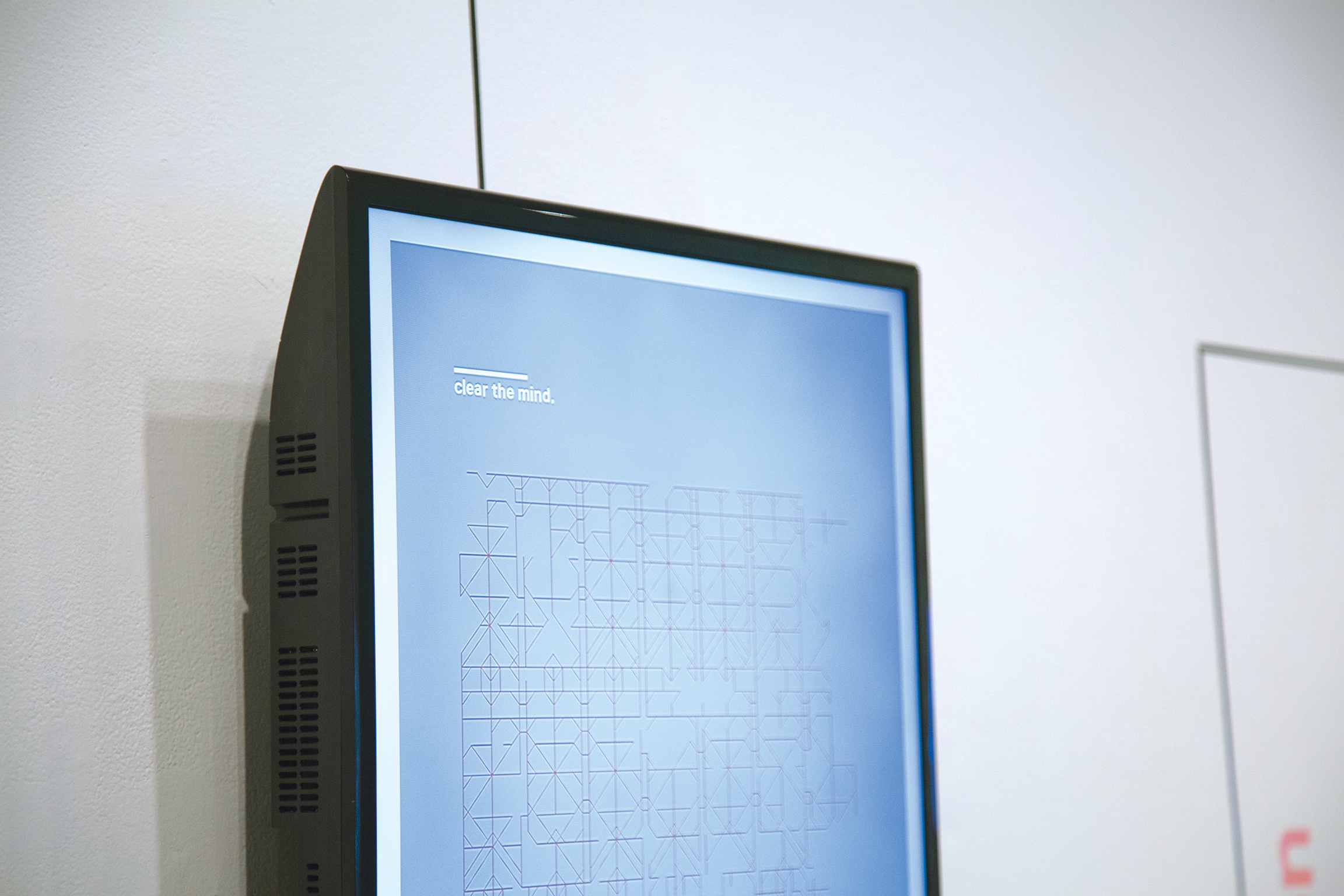

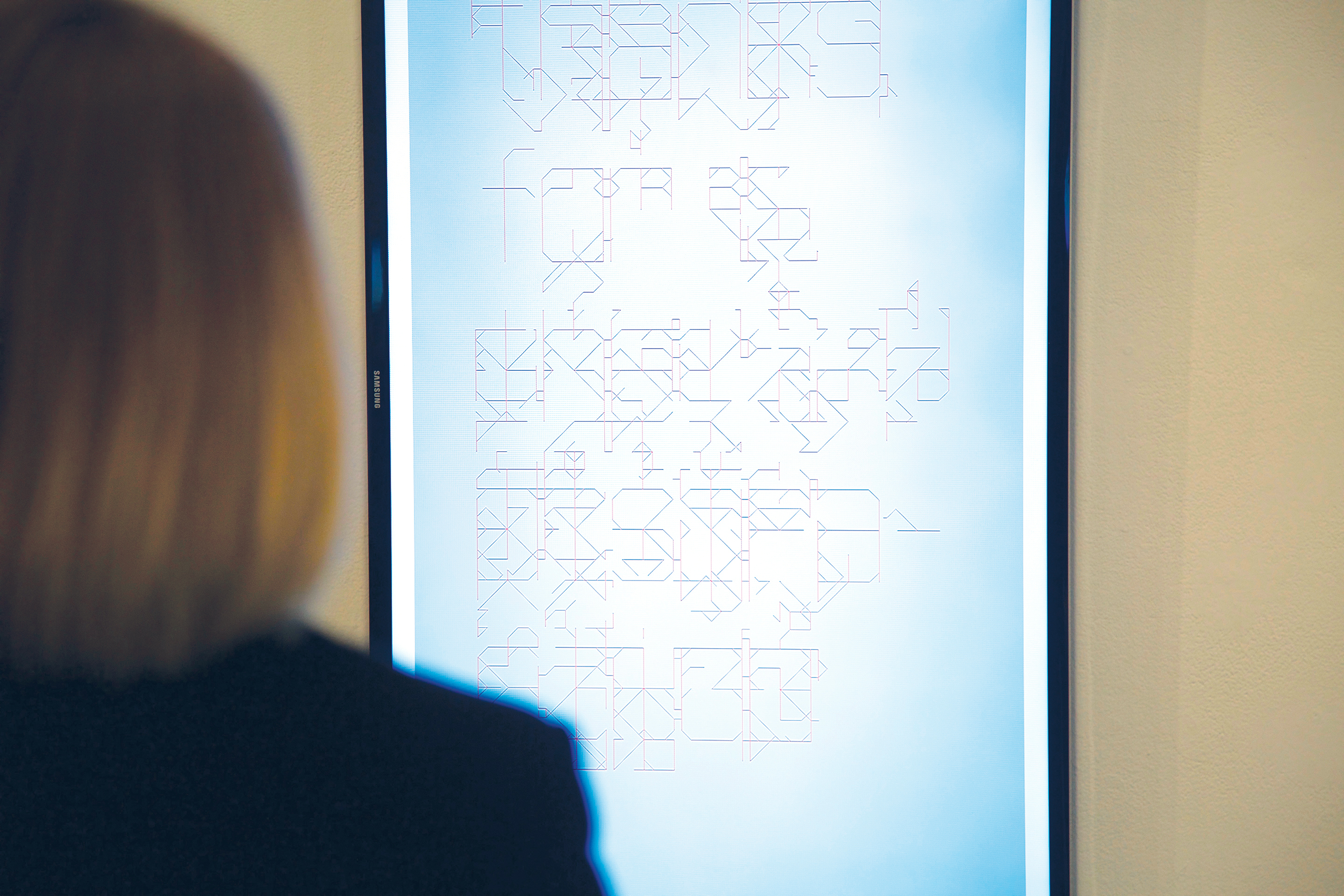

Next is an interactive digital poster. As in the timelines, lines forming this grid represent thoughts; in this case an overwhelming tangled grid of thoughts. But the messy lines shrink away as a viewer approaches, leaving only one clear, positive, thought. These final messages change regularly, and the direction of the growing lines evolves every time it animates. Hence, a viewer’s physical presence affects the visuals.

The purpose of the interaction is two-fold: on one hand it acts as an entry point to a difficult topic. When viewers realize they impact the piece, they spend more time with it. Second, the interaction serves as a metaphor: your presence in a patient or survivor's life makes a difference.

This custom typeface was designed using only 90- and 45-degree angles. This means overlaying numerous letterforms (representing thoughts) ultimately creates a web-like grid. The tangled grid slowly clears away as a viewer approaches, representing a clearing of the mind.

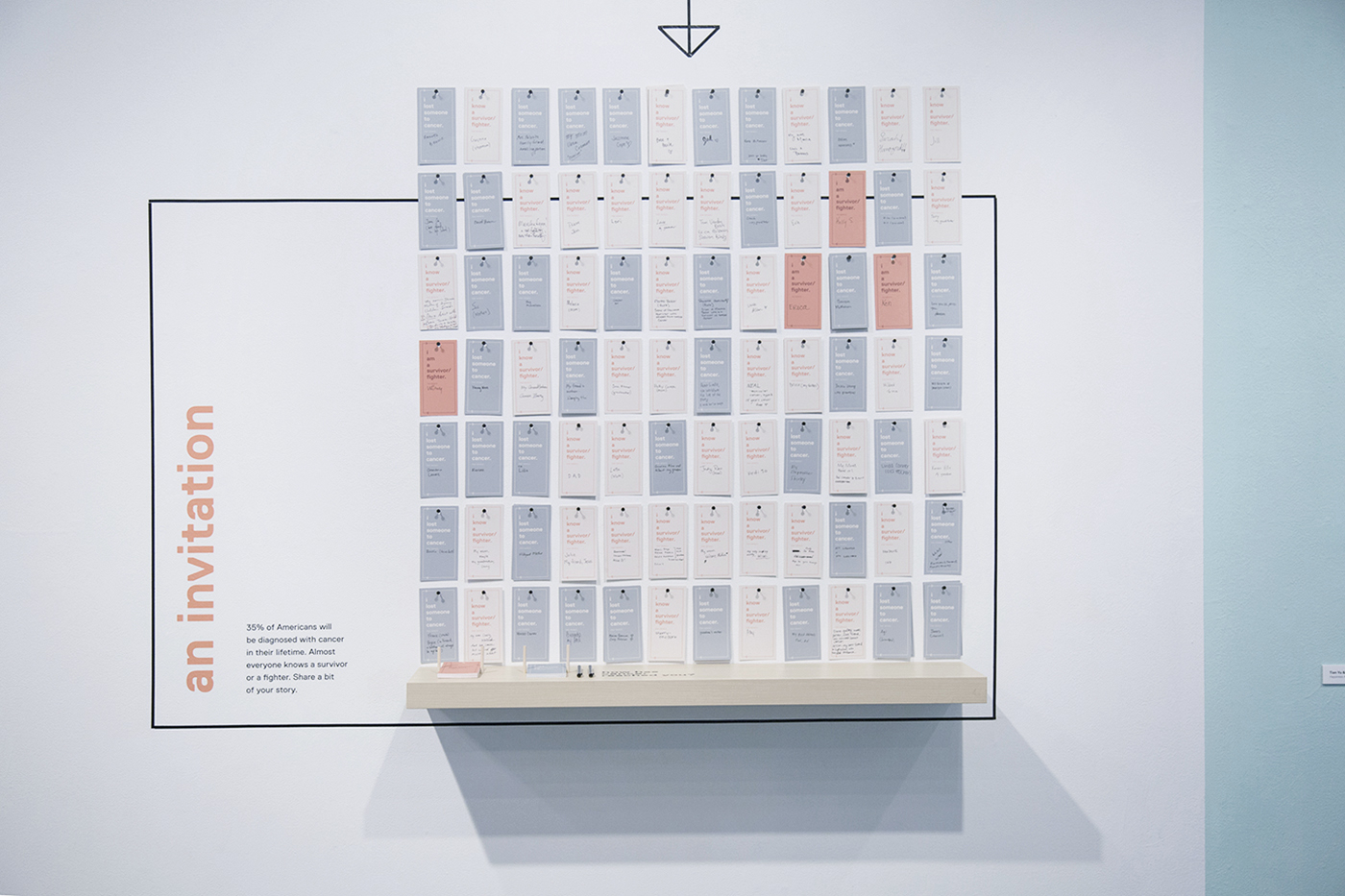

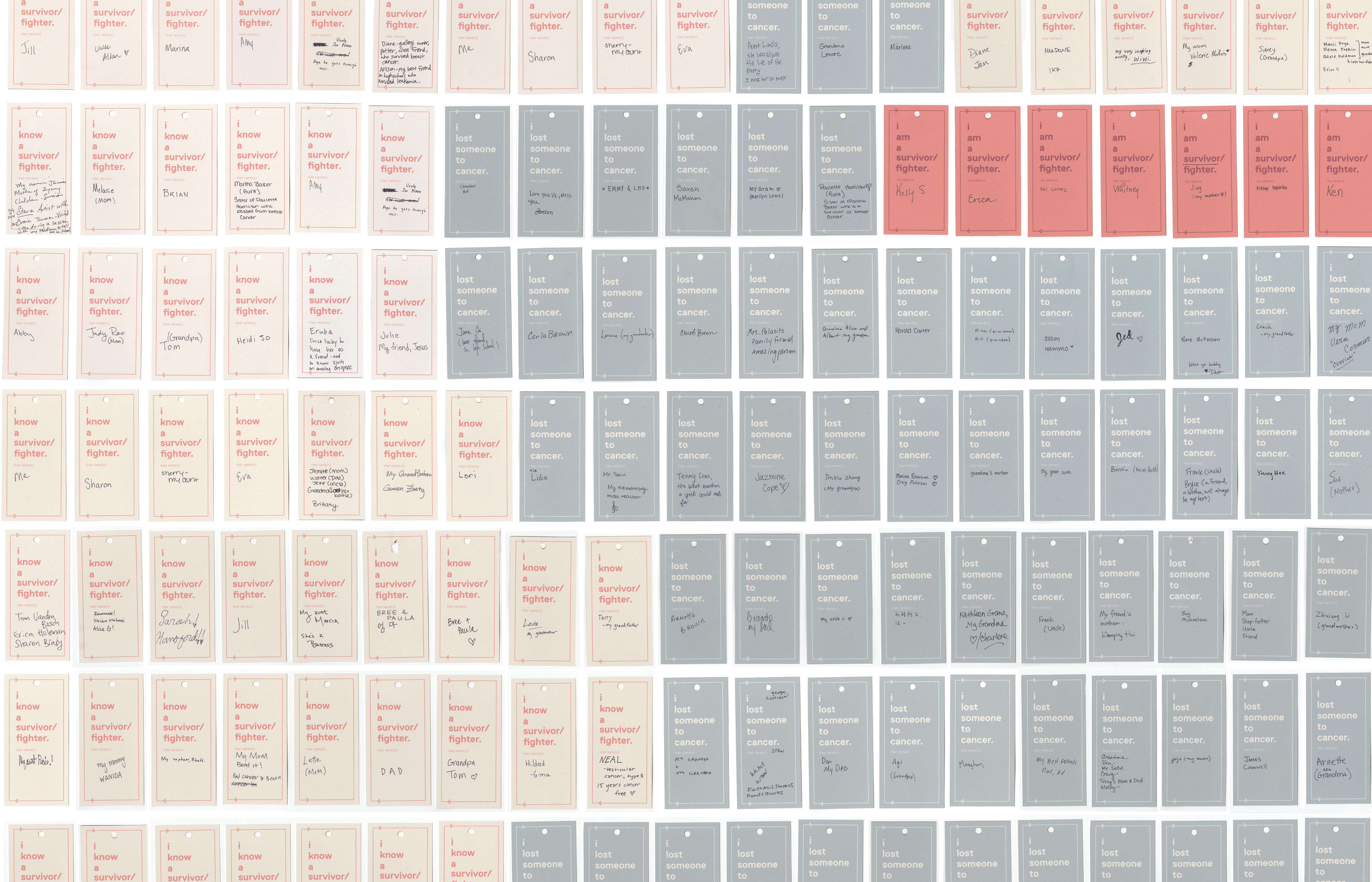

section three: an invitation

After viewers heard from patients and saw their own impact, they had a chance to respond — to add their voice to the piece. In the final section of this exhibition, visitors left the name (or names) of those they know affected by cancer. During the two-week show, visitors left more than 120 responses.